Stillman Waters Run Deep

Dear friends,

When I told my friend Claire (hi Claire!) that I was working on a long piece about Whit Stillman for no reason at all she said, "I feel like that's been growing in you for a while." It's true that I love, really love, Stillman's chatty, posturing, accidentally cool movies. But particularly now his films resonate with me in a new way. Seeing yourself in a Whit Stillman movie is not flattering, and this most recent iteration was even less so. I promise this long form is an anomaly! I've got drafts of future newsletters for barnyard animals, motorcycles, housewives, therapy, and some others too. But for now, if you care to read a rambling about disco and race riots and class envy, here we go!

Four years ago this month, I left Seattle. After the end of a tumultuous relationship with "the libertarian," I was without an apartment, which I used as a point of persuasion when asking my bosses at Wave Books if I could spend the summer networking for the press in New York. Honestly, after a decade, I was sick of Seattle and its intentional quaintness. A former Wave intern and friend, Candystore (mentioned in the previous newsletter), hooked me up with a sublet in their Bushwick spot, a four bedroom with a rooptop patio, where I would smoke joints by myself in the humid, languid nights.

I took myself out to the movies to pass time. The Last Days of Disco (1998, directed by Whit Stillman) was playing at Metrograph, a chic movie theater owned by a tie designer in the Lower East Side with remarkably plush disposable bathroom hand towels. I'd already seen Stillman's first film, Metropolitan (1990), about ivy league socialites and their post-debutante-ball soirees. From my prophetic review in an email to my friend Richard: "I liked Metropolitan! It did sort of make my skin crawl. The ignorance of the characters is pretty appalling but somehow the fact that they're teenagers makes it a little better; until you realize that they'll probably be that way forever and grow up to be gross libertarian bankers!" Despite my hesitation, and misunderstanding, of Stillman's voyeurism of the obnoxiously literate uppercrust, I went because I am to disco what bears are to honey (or garbage).

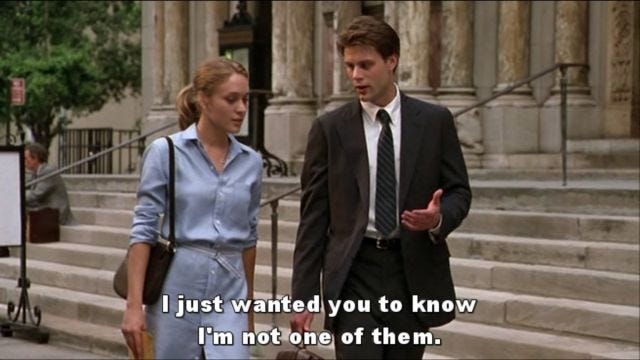

The Last Days of Disco is about a shy recent Hampshire graduate, played by Chloe Sevigny, who works as a grunt in a publishing company. She moves into a cramped and decrepit railroad apartment with her brash, manipulative coworker and what we now call a "frenemy" from college, played by Kate Beckinsale. They spend their nights at a popular disco that a friend manages. He went to Harvard, Stillman’s alma mater. In fact, several of their friends go to The Club, also all male Harvard graduates; seemingly it's the only place they all go, where they occasionally dance and flirt and mostly throw verbal darts at each other.

Sevigny was just off of making Kids when Stillman started production on Last Days. The studio wanted big names, and the role was originally offered to Wiona Ryder, but then was given to Sevigny who nailed her late audition. Beckinsale said, “She had this very fancy fur coat of a social life that she wore very casually and was very happy for you to try on.” But Sevigny plays the lonely ingenue with grace. My favorite scene in the film is of her character’s clumsy seduction. It’s deliciously awkward and charmingly erotic; ”there’s something really sexy about Scrooge McDuck” she says with forced confidence before downing a glass of Pernot. This is when Stillman shines. His films are, he himself admits, romantic comedies. They have an intellectual veneer but they are romantic comedies nonetheless, with the same soothing will-they-won’t-they lull as any other.

It’s the last film of Stillman’s unofficial Doomed Bourgeoise in Love trilogy, following Metropolitan and Barcelona (1994), about two American cousins in the titular city during “the last decade of the Cold War” fumbling about with Spanish women and dodging accusations of being fascists. Each film is set on the teetering edge of an era but the focus is not the politics of the time. His influences are Jane Austen, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Oscar Wilde. Like them, he enjoys puppeting his witty, blueblood characters as reacting to social change, not bearing responsibility for them. There is a higher stakes drama about the club in Last Days itself involving large bags of cash and drugs and undercover agents—mirroring the fate of Studio 54, where Stillman used to party—but as with all of Stillman’s films, the fate of many is only a backdrop to the existential romantic drama of a few.

Despite all their good looks, social status, citizenship, and money, they are plagued by outsider complexes. They know that they are despised by everyone: the working class, the nouveau riche, the hip and the square, each other, oh and also the rest of the world. They whine that there really is a discreet charm in the bourgeoise and the “no yuppies” rule of the club is akin to Nazi Germany. The Last Days clique, having hatched out of prep school and small college towns, are developing in the primordial ooze of the club for only a short time until they're able to drive out and into their suburban homes. In their suits and sweaters, bobbing to the music, they stand out like sunbleached buoys amid the sea of glittering half naked stunners in an assortment of skin colors. They are “nostalgic for the present,” Stillman says, painfully aware that these are the “Good Times” Chic sings about, the one time in their lives when they can question their identities and socialize with people unlike themselves, even if ultimately they choose the claustrophobic safety of their group.

Disco was a joyous movement by and for minorities, particularly minorities of color and gays and women and the poor in cities that were devastated by racist and greedy public policy. A breakthrough and exemplar, "Love Train" by the O'Jays entered the Billboard's top 40 in 1973, on the same day of the Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Viet Nam. It's known as the first disco song to chart. The chorus sings, "People all over the world / join hands / start a love train (a love train)." It was a peaceful and celebratory musical respite that was open to all. But alas, disco followed that familiar fate: movements and spaces created by minorities are overtaken first by whites who just want in on the fun, then co-opted and gentrified by money, and finally deemed passe by white culture, well past when the originators have been pushed out.

The stand-in white working class character of Last Days is the snob of the publishing company and union organizer who chides the girls for their parental allowances and quest for a best-seller book, a playground flirting technique. He’s brought into their clique by dating one of their members, which means his presence is expected at the club. He makes thin protests about going to a disco, eventually admitting that he doesn’t think he’d get in. “Of course you’ll get in, Holly’s gorgeous,” and they’re right, his proximity to status is his key. Inside the club, his curmudgeonly defenses melt, and he dances with the gleeful feeling of acceptance he thought he’d never get. But it’s temporary, of course; he’s not really one of them. When he accuses the girls of only wanting to marry for money, Beckinsale bites back that it’s a better option than marrying someone like him. Flustered, he lobs his only weapon: “Disco sucks!”

In 1979, over 50,000 people came to see Disco Demolition Night at Chicago's Comiskey Park. Organized by talk show host troll Steve Dahl and WPUL, the event was a promotion for a doubleheader game between Chicago White Sox and the Detroit Tigers; admission was discounted to 98 cents for attendees who turned in a disco LP. In-between games, the records were put into a crate and exploded. The display turned into a riot when the audience of white men stormed the field. They set fires and clashed with police. The playing field was so damaged that the White Sox were required to forfeit the second game to the Tigers. I’m vastingly oversimplifying for brevity here: not just a blue collar statement against the femme glitz of disco that would roll into the wealth worship of the 80s ala Dynasty, it was an explosion of simmering resentment of the basic freedoms given to women and black people of America after the civil rights movement and women’s lib; an African-American usher, Vince Lawrence, told NPR that he saw “records that were black records...Curtis Mayfield records and Otis Clay records.... Records that were clearly not disco.”

But this is not really a film about disco and what it stood for. As Luc Sante says about Metropolitan, but can be applied to any of Stillman’s films, “The movie certainly does not concern itself with political questions—the actual money and power that lie behind the cultural anxiety and ritualistic tinsel of the upper bourgeoisie go unmentioned—but it is, after all, a movie about kids.” The kids of Last Days make no mention of the fact by 1984, over 12,000 people have died of AIDS, primarily gay African-Americans and Latinos as reported by the CDC. Stillman’s characters glide on razor sharp wits over thick ice, daring to be plunged into the “real life experience” they so crave in which they would surely drown. The only mention of homosexuality is by the character who professes to be gay to end his romances. A character contracts herpes. They pick up their prescription at the pharmacy, looking forlorn, and there’s a brief discussion about how it could actually be a good thing for their romantic prospects. Either she’ll find a guy who’s been around so much he has it too, or someone will be so in love with them that they won’t care, choosing to contract it themselves as a lifelong bond.

Stillman made the movie as a warning for his daughters he says; “I wanted to, you know, advise them to watch out for some things.” He’s perhaps not wrong but he’s so damn earnest and prudish about it. Each film in the trio features some grappling with the fallout of sexual revolution, the moral always being that sexual freedom is only detrimental to women. Women, now with a lot of choices, are free to make a lot of bad choices. They pine for the nice guys who in their youthful ignorance prefer liberated women and are forever traumatized. They pine for the womanizers who cheat. They do a lot of waiting for men to come to their senses and hopefully they’ll have saved their purity for when the nice guys realize they actually want a simple girl to settle down with.

Leaving the movie theater, I recognized a writer. She gave me a coy smile, I'm assuming acknowledging that she knew that I knew who she is. Maybe she was smiling at the cliche of two women in New York publishing seeing a movie about two women in New York publishing. Despite how corny and probably imagined this nonverbal interaction was, I was exhilarated. A few months later, her husband, a famous magazine editor, rubbed up against me at a party in a way that was clearly violating but hard to describe.

After all this, it might come as a surprise that I love this movie so much. I watch it every year for my anniversary of moving to the city. This year's screening was particularly unsettling. As my colleagues and work friends have abscond to their family’s second homes, or are communing with their posh friends in the country, I’ve been calling my dad to make sure he’s getting unemployment checks on time. There is a temptation to, like the one poorest friend in each Stillman film, resent and envy what my peers have that I do not. What could be more short sighted during a time, like in Last Days, when people are getting sick and dying due to the racism and incompetence of government, the police are killing in the streets, and white bitterness threatens us all. From a wider lens, do I not have more in common with my more affluent peers than those who are suffering? I have a job that I enjoy, a home which is safe and comfortable, a loving partner, money to buy occasional pleasures, wonderful friends who check in on me when I’m feeling blue. The goal is not to have everything I want, but to help others get their basic human rights, which requires an occasional reminder that I already have everything I need and more and my energy is better served looking beyond the social sphere of the dinner party circuit.

“Love Train” is the last song of the film, which plays as ordinary New Yorkers gaily dance in the subway. It’s a touching, optimistic final note, and I admit I teared up as I rewatched the film this week, strangely nostalgic for, I don’t know, the unglamorous banality of life outside with other people. If you’re craving the drama of nightlife, or reminiscing on a scene you gave up long ago, perhaps an escape from our times and a mirroring of them, I highly recommend that you watch Last Days of Disco, preferably in your finest attire, sipping a vodka tonic with a grain of salt.

Love,

Brittany